Getty Images

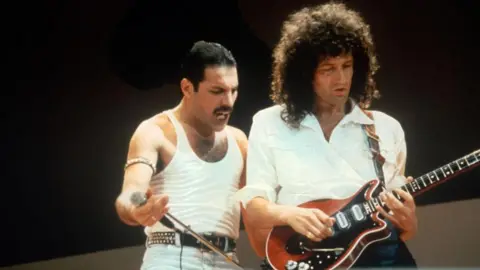

Getty ImagesQueen guitarist Sir Brian May says new research shows cattle could be passing bovine tuberculosis (bTB) between themselves, and that badgers are not a significant factor in the spread of the disease.

Sir Brian, 77, helped conduct the research presented in a new BBC documentary, and says his campaigning against badger culling to tackle bTB “has become as important to me as music”.

Cattle are regularly tested and destroyed if the disease is found, with more than 50,000 slaughtered in the UK between April last year and March this year.

A leading vet said Sir Brian’s findings could not be viewed in isolation, while a farmer who has lost 500 of his herd to the disease said badgers “do contribute” to the bTB problem.

After the commissioned research which took more than 10 years, Sir Brian said he believes that improving farm hygiene could help to provide a solution to the problem of bTB.

“The spread of bTB is from cow to cow and it’s because of inefficient hygiene situations. Biosecurity in the old days meant keeping the badgers out but now means keeping the slurry away from the cows so they can’t infect each other,” Sir Brian said.

After working with farms in Wales and England, he concluded that the pathogen which caused the spread of bTB was present in large quantities in the faeces of cattle which can contaminate food and water for the animals.

“At the root of it all there are certain principles which need to be followed which are really keeping the pathogen from progressing throughout a herd, cutting off its line of transmission,” Sir Brian said.

“Everything is within the herd.”

BBC | Athena Films | BBC Inside Out

BBC | Athena Films | BBC Inside OutSir Brian said he didn’t blame the farming community for the “suspicion and hostility” he had experienced upon presenting his ideas to them, but said he thought his team could “make a change and offer hope”.

“We’ve been 12 years on this trail and we’ve made discoveries which no-one else has made,” he said.

“Speaking out against the culling of badgers has become as important to me as music.”

But Wales’ former chief veterinary officer Christianne Glossop said that while slurry management was important in tackling bTB, it was hard to achieve on some farms and should not be viewed in isolation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMs Glossop, the new chairwoman of the Royal Veterinary College, said: “TB can arrive on a farm through an infected animal, through dirty boots being walked on to a farm, indeed the possibility of infected slurry being spread in the fields next door.

“It’s also possible that other infected species, including the badger, may introduce infection onto a farm.”

Working with vet Dick Sibley at Gatcombe Farm in Devon, Sir Brian’s research suggested that the standard bTB skin test did not detect all instances of the disease in cattle that could be captured with enhanced testing.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs a result, he said herds or bulls that were considered bTB free could in fact have been spreading the disease.

While analysing cattle faeces, the bTB pathogen M. Bovis was found.

The farm introduced a new hygiene regime, to keep the faeces from contaminating living areas, food and water.

After four years in 2019, the farm became officially bTB free.

Ms Glossop paid tribute to Sir Brian’s work, but added: “Did that case study prove that badgers have no role to play in the bovine TB equation? No, I don’t agree with that conclusion.”

Farmer Chris Mossman has had more than 500 cows destroyed after testing positive for bTB at his farm in Llangrannog, Ceredigion, since 2016.

“It’s very interesting what Brian May and Dick Sibley have done, but my opinion of TB is that it’s a very complex, complicated disease,” he said.

“It’s running rings around all of us because the situation is not improving. My way of thinking is, pursue it, let’s roll out onto other farms to see if they have an equal level of success with it, but we can’t put all our eggs in one basket.”

Mr Mossman said dealing with bTB in his herd had taken a toll on his mental health and following testing procedures and biosecurity measures required of him and his staff “imposed almost another job on top of our daily job just to cope with this disease”.

A trial badger cull was established in the 1990s to assess its effectiveness in controlling bTB.

Lord John Krebs, who was behind that 10-year scientific trial, told the programme: “If you really want to control TB in cattle then killing badgers is not going to be a terribly effective policy.”

In 2011, the UK government decided to cull badgers in TB hotspots in England because – after re-interpreting the Krebs evidence – it concluded badgers could be contributing to the spread of bovine TB.

Between April 2023 and March 2024, more than 21,000 cattle were slaughtered in England after bTB was found, with 11,197 animals killed in Wales and 18,577 in Northern Ireland.

Scotland is officially bTB free and incidence is very low.

Labour pledged before last month’s general election to look at new ways to tackle bTB spread “so that we can end the ineffective badger cull”.

The UK government said it was working towards a situation where badger culling could be ended in England.

BBC | Athena Films | BBC Inside Out

BBC | Athena Films | BBC Inside Out“We recognise the devastating impact bovine TB has on the farming community which is why we are committed to beating this insidious disease,” said the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

“This government will roll out a TB eradication package including vaccination, herd management and biosecurity measures to achieve our objective of getting to bovine TB free status and end the badger cull.”

Of the 11,000 cattle killed in Wales last year, nearly 40% were in Pembrokeshire.

Last week, the Welsh government established a board in an attempt to reach a TB-free Wales.

The Welsh government said it was “very aware of the distressing impact of bovine TB on the health and well-being of our farmers and their families and we are absolutely determined to eradicate this devastating disease”.

Brian May: The Badgers, the Farmers and Me is on BBC Two at 21:00 BST on Friday and on the iPlayer from that day